ISLAMABAD (AP) — Pakistanis braved cold winter weather and the threat of violence to start voting for a new parliament Thursday even as the death toll from twin bombings a day before claimed at least 30 lives, in the worst election-related violence ahead of the contested elections.

Tens of thousands of police and paramilitary forces have been deployed at polling stations to ensure security. Still, on the eve of the election, a pair of bombings at election offices in the restive southwestern Baluchistan province killed at least 30 people and wounded more than two dozen others.

The balloting has also been marred by allegations from the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party of imprisoned former Prime Minister Imran Khan that its candidates were denied a fair chance at campaigning in the runup to the vote. The cricket star-turned-Islamist politician — ousted in a no-confidence vote in parliament in April 2022 — is now behind bars and banned from running but still commands a massive following. However, it remains unclear if his angry and disillusioned supporters will turn up at the polls in great numbers.

The election comes at a critical time for this nuclear-armed nation, an unpredictable Western ally bordering Afghanistan, China, India and Iran — a region rife with hostile boundaries and tense relations. Pakistan’s next government will face huge challenges, from containing unrest, overcoming an intractable economic crisis to stemming illegal migration.

The weather on voting day was cold but clear. Mobile phone service was suspended temporarily after the previous day’s bombings. The statement from Pakistan’s Interior Ministry said the decision was made to maintain law and order. It did not say when the suspension would be lifted.

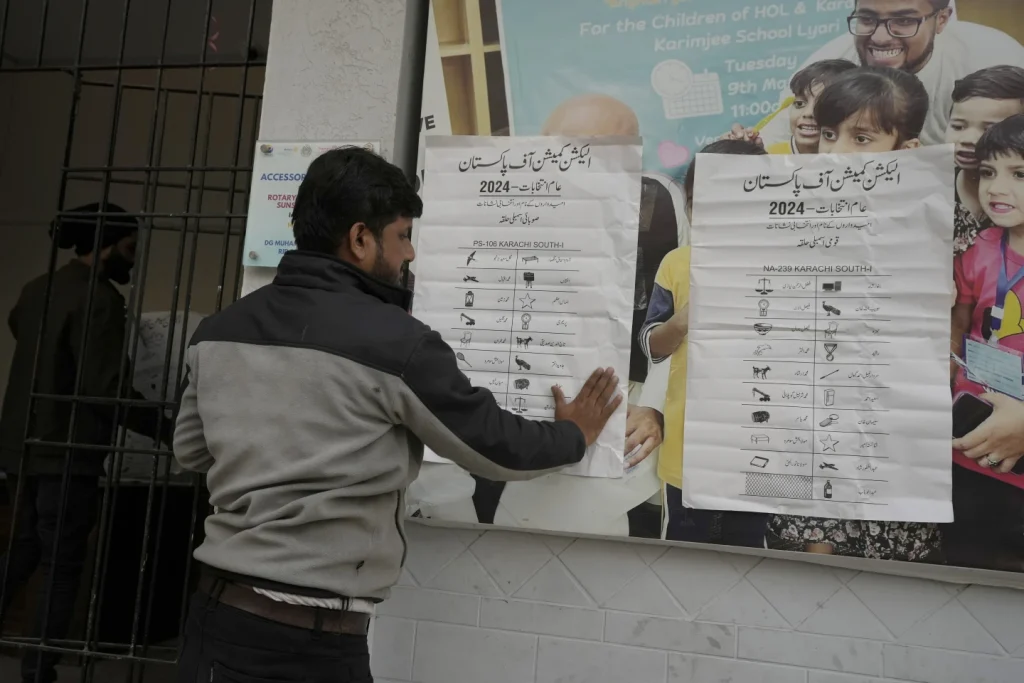

As many as 44 political parties are vying for a share of the 266 seats that are up for grabs in the National Assembly, or the lower house of parliament. An additional 70 seats are reserved for women and minorities in the 336-seat house.

After the election, the new parliament will choose the country’s next prime minister, and the deep political divisions make a coalition government seem more likely. Separately, elections are also taking place Thursday for the nation’s four provincial assemblies.

The last time parliamentary elections were held in 2018, when Khan came to power, a little more than half of the country’s electorate of some 127 million voters cast ballots. If no single party wins a simple majority, the first-placed gets a chance to form a coalition government, relying on allies in the house.

The top contender is the Pakistan Muslim League party of three-time former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif who returned to the country last October after four years of self-imposed exile abroad to avoid serving prison sentences at home. Within weeks of his return, his convictions were overturned, leaving him free to seek a fourth term in office.

With his archrival Khan sidelined and in prison, Sharif seems to have a pretty straight path to the premiership, backed by his younger brother, former Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, who is likely to play an important role in any Sharif-led Cabinet.

The Pakistan People’s Party is a strong contender, with a power base in the south, and is led by a rising star in national politics — Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, the son of assassinated former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto.

The Sharifs and Bhutto-Zardari are traditional rivals but have joined forces against Khan in the past, and Bhutto-Zardari served as foreign minister until last August, during Shehbaz Sharif’s term as premier.

If Khan’s supporters stay away from the polls, analysts predict the race will come down to the parties of Nawaz Sharif and Bhutto-Zardari, both eager to keep Khan’s party out of the picture. As Bhutto-Zardari is unlikely to secure the premiership on his own, he could still be part of a Sharif-led coalition government.

For Khan, convicted on charges of graft, revealing state secrets and breaking marriage laws — and sentenced to three, 10, 14 and seven years, to be served concurrently — the vote is a stark reversal of fortunes from the last election when he became premier.

Candidates from Khan’s party have been forced to run as independents after the Supreme Court and Election Commission said they can’t use the party symbol — a cricket bat on voting slips — to help illiterate voters find them on the ballots.

The undoing of Khan and the resurrection of the Sharif political dynasty have given the impression of a predetermined outcome, and “it may be too late to change that perception,” according to Farzana Shaikh, an associate fellow at the London-based think tank Chatham House.

On Tuesday, the United Nation’s top human rights body warned of a “pattern of harassment” against members of Khan’s party, which claims it was subjected to a “reign of terror” and that it has been prevented from holding hold rallies like Sharif’s party. Authorities deny the allegations.

Pakistanis, like people in many other impoverished nations, grapple with sustained high inflation, rising poverty levels, daily gas outages and hourslong electricity blackouts.

Since Khan’s ouster, Pakistan has relied on bailouts to resuscitate its spiraling economy, with a $3 billion package from the International Monetary Fund and wealthy allies like China and Saudi Arabia jumping in with cash and loans.